A quick guide to image files

Know your image files, embracing behavioural science, Apple’s new M3 chips, and a new way to search for info

Visual media grabs attention, images can be used as entry points to content, and content that contains imagery can be more appealing to look at. Which explains why the majority of content published to audiences contains photographs, graphics or illustrations.

However, although content producers are used to working with images, and some social platforms, such as Instagram, are defined by their images, many people are confused or uncertain about how image files can differ. And which image files they should use when publishing different types of content and media.

For example, it is very common, even for communication specialists working within large corporations, to share brand logos as .jpeg files. And assume these files can be used by colleagues. The reality is that often they can’t - for reasons we’ll explain below.

That simple misstep can lead to significant confusion, frustration and time wasted as staff try to work out why the brand logo they’ve been supplied, and placed on their presentation or report, is displaying a large, unwanted white square behind it they can’t remove.

So here is a short handy guide to the most commonly used image files.

First we must highlight the difference between images based on pixels, and those based on vectors.

Software such as Photoshop produces raster files, which record pixels, storing an image as a series of tiny coloured squares. If you size up these files too large, eventually you will see the image pixelate and lose definition. Photographs are usually saved as raster files exported to .jpeg, .png or .tiff file formats, while .gif files also contain a series of raster images.

Other software, such as Illustrator, produce vector files, which use mathematical code to create the same image at any scale. So vector files will look crisp at any size. Vector files are then exported to either .pdf, .png files, or to the .svg file format.

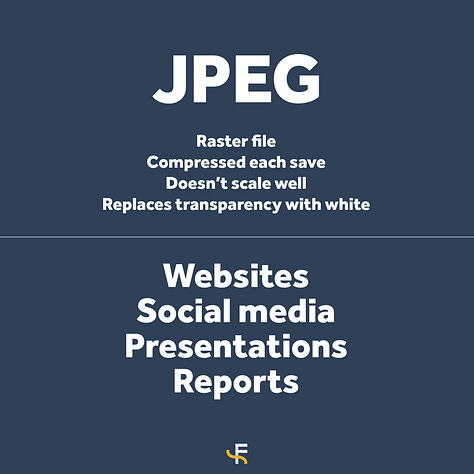

JPEG

.jpeg or .jpg is perhaps the most common file format used to save and share images.

Note that .jpg is the older, more limited format, and .jpeg is the current standard. These files are commonly used to post images to websites, blogs and social media, and placed in presentations and reports.

Images saved as .jpeg files are compressed. Be aware they can be further compressed each time the file is saved. So check the quality of the image files you want to use in your content, to ensure it is still acceptable.

Note the .jpeg format always includes a background, adding white to replace any transparency. Usually you don’t see this, as your image fills the image canvas, reaching all four edges. However, if you place a smaller image on a larger canvas, or you add an image that has transparent elements, the export process will fill those spare spaces and elements with white.

That’s why it’s a bad idea to share logos as .jpegs. Logos usually contain negative space, either between the letters of written logos (known as a Wordmark), such as Google’s logo. Or around a non-rectangular logo symbol (Brand Mark), such as Nike’s swoosh logo. This negative space should be transparent, so the logo can be placed on top of other images and designs.

.jpegs are raster files.

PNG

An image saved in the .png format maintains its size and quality throughout multiple saves and changes.

Another benefit is that the .png file format can maintain transparency, so you can cut content out from images, and save it as a .png file without a background. This can then be overlaid onto other content. Logos are best shared as .png files or .svg files (see later).

.png files are lower in resolution than other image file types, so are better for digital media than printed images.

.pngs are raster files.

TIFF

The .tiff file format can be used to save and print high quality images, and is best used in creating documents or content to be printed rather than digitally published, which usually requires smaller file sizes.

.tiffs are raster files.

GIF

The .gif file format can support short animated graphics, short clips or moving images.

.gifs are raster files.

SVG

The .svg file type is most common in website design. If you’re designing a logo or graphic for a website, you may work with SVG files. This extension supports smaller image files and short animations. This file type maintains a clear resolution at any scale.

.svgs are vector files.

PDF

PDF is the portable document format, saved as .pdf.

An image can be saved, shared and published as a .pdf, which is why we are including pdf in this list. However, that is less common.

More usually, .pdf is a popular file format for sharing documents.

A .pdf preserves the original layout, formatting and design of a file, and can be printed, emailed and scanned relatively easily. Though possible, it can be harder to extract information back out of a .pdf file to use in other software, so this file format is usually used to capture a final document, report or magazine that will be viewed by an audience, but not interacted with or altered.

However, it’s worth knowing that .pdfs are based on a similar technology to Adobe’s Illustrator software, which produces .ai files. That means .pdfs can be converted to .ai files, and edited in that software, relatively easily.

.pdfs can contain both raster and vector-based images.

For more information, enrol in the Factual Storytelling School and take our lesson Know Your Files and Codecs.

Embrace Behavioural Science

Our recommendation this week? That as well as subscribing to, following and recommending The Factual Storyteller, you review the archive of “A Load of BS: The Behavioural Science Podcast”.

At the Factual Storytelling School, we’re big advocates of drawing insights from behavioural science, and using that information to better reach audiences.

To truly impact audience, you need to understand how they behave, make decisions and what stimuli they best respond to. You’ll hear us talking about it a lot, and we’ve previously recommended you follow Behavioural Scientist Patrick Fagan.

Apple’s new M3 chips

When it comes to content production tools, we’re not going to re-open the age-old Mac versus PC debate - and we suspect we may not change anyone’s mind about which is better even if we did.

Instead, we’re highlighting that Mac’s new M3 chips, that power the company’s latest MacBook Pro and iMac models, have been available for a few months now, since their launch in late 2023. And that’s enough time for reviewers to have trialled the chips, and provide insights into whether Mac-using content producers should consider upgrading their hardware.

Before Apple started integrating its own chips into its products, content producers were in a bit of a bind. That’s because Macs with high chip speeds, had fewer processing cores. And those with more cores, had slower chip speeds. That created a dilemma for multimedia producers.

Higher chip speeds allowed for faster working, and a computer that could design and edit more quickly. But they are slower to render out and export the resulting final files. More cores rendered large files, such as long-form videos, or videos containing lots of effects or animation, far quicker, but were slower to drive design and video software, as they were combined with slower chips.

So you could either work fast, and wait a long time for your file to export, or work on a slower computer that exported the final file far more quickly.

Apple’s M-series chips have reduced this issue - and use multi-cores and multi-threading to far more effectively process and render content.

PC Mag has published a detailed review of how the latest generation M3 chips stack up in terms of raw performance, which you can read here.

A new way to search information

When you want to research your factual story online, there are generally two ways to go about it.

You can take the conventional approach, open a web browser and use a search engine to find web links and pages related to your request.

Or you can use an AI chatbot to search the web for you, and summarise the information it has found.

Increasingly, you should learn to do the later, and start to harness the power of AI to more efficiently research factual content. It’s a topic we’ll return to, with tips and techniques about how to best use AI in your communications work, and just as important, aspects of using AI that you should be wary of.

But for today, we’re highlighting a new development in how to use the dominant Google search engine to research your work.

Google have just launched a new search tool, called Circle to Search. It works only on Android phones. But it offers, in the company’s words, “a new way to search for anything on your Android phone without switching apps.” It’s particularly useful for searching for information about objects in images and video.

You activate Circle to Search by long pressing the home button or navigation bar on your Android phone. You can then circle any item you see in a visual image. The tool will then find similar items from across the web. Circle a watch in an image, and it’ll return information about it, including links to retailers selling it.

You can ask more complex questions about what you see.

Circle a food and ask “is this nutritious?” and Google will provide information from across the web. Or you can circle phrases or words shown in videos or images to learn more about what those expressions mean.

Circle to Search is, of course, powered by AI.

If you want to know more about how a range of Google’s AI-powered tools can help you research your work, this blog by Google is a good place to start.

We recommend you do.

For example, you can find out how you can point your camera and ask the Google app to answer questions you have about what you are filming, among other techniques.

You can also read here our coverage of Google’s new Pinpoint tool, that allows you to search thousands of documents.

Subscribe for more future updates about how we can help you use such remarkable new technology to tell your story, and that of your organisation.

And don’t forget to consider enrolling you or your team or organisation into the Factual Storytelling School course.